Is Thought Elsewhere?

Perhaps it is time for us to consider how the privileging of writing crafted elsewhere might have impoverished writing crafted at home, by caregivers

Is Thought Elsewhere?

Last year, a rest residency for single mothers that provided for a week’s free stay at an old knitting factory in rural Ireland, along with a childcare stipend, received over 700 applications. The residency’s call for applications went mildly viral; people loved its generosity of spirit, its accompanying childcare stipend, and its acknowledgement of the hard and lonely work that goes into single-mothering. The residency was founded by bestselling author Betsey Cornwell, a single mother herself, who left an abusive marriage and then created the Old Knitting Factory Retreat to provide a space for other creative single mothers to be able to nurture themselves, their children, and their art.

I, like so many others, loved the idea of the residency, and its generosity.

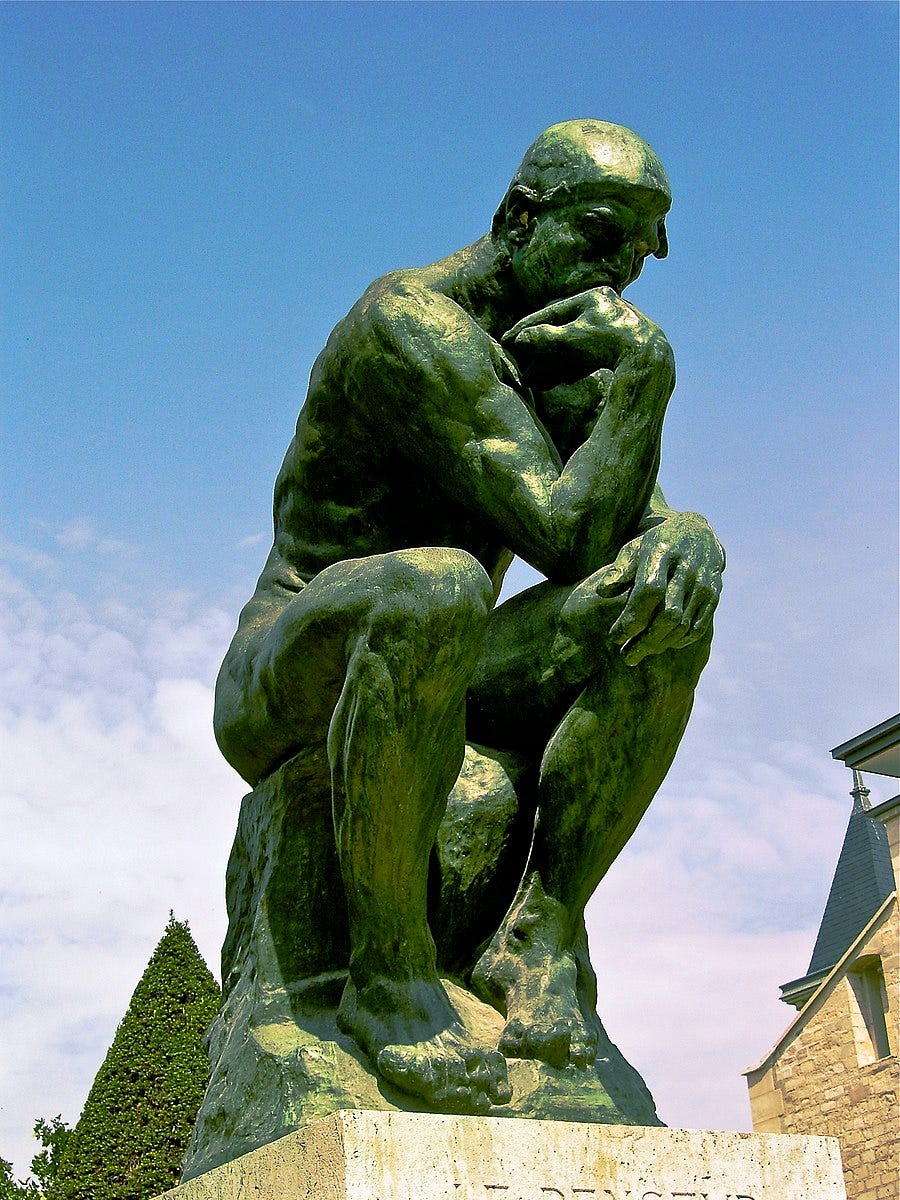

The Thinker, Paris, photograph by Andrew Horne, from Wikipedia Commons

The idea of a week in rural Ireland at an old knitting factory, where I could take my child, rather than leave her behind, seemed like a dream. In particular, I was struck by the providing of childcare, by the allowing of children. This is something that I have rarely seen in the descriptions of the many other writing fellowships I keep perusing, keep applying to, hoping wistfully for an open horizon of my own — any length of time to spend with my own words and ideas, in the midst of a busy, rewarding, precarious, untenured academic career built out of teaching first-year writing to hundreds of students, for over a decade, and across two continents.

It has been quite a decade. I birthed a child, then played a central role in birthing a brand-new, built-from-scratch University in India, grappled with the vagaries of thyroid cancer, grappled with the still-more difficult vagaries of divorce, built institutions, built programs, moved countries, once, twice, thrice, became a reluctant re-immigrant in my mid-40s, and through it all read and nurtured the words of others, thousands of words from hundreds of students, always trying to remember to hold every essay, every student, precious. After a decade immersed in that immense ocean of words, it is easy to forget. That is something I do not allow myself.

It has been a lot.

Far less than most, who experience far worse each day — I acknowledge my many layers of privilege in a world where unspeakable things are taking place every second — but some more than many. Like many single mothers, I’m burnt-TF-out.

Oh Lord won’t you buy me a Mercedes Benz, my friends all drive Porches, I must make amends, goes the Janis Joplin song (listen to it — possibly the greatest song ever written about coveting — now, if you haven’t already).

Oh Lord won’t you buy me a writing retreat, my friends all have tenure, I must find a lender, goes my song, to the same tune.

So with that refrain in my head, I continue to teach, dedicatedly, carefully. But I keep on writing and keep on applying and keep on getting rejected from both academic and non-academic fellowships.

I apply for time, but I keep seeing place.

New Mexico. Berlin. Bellagio. Philadelphia. Provincetown. Seoul. Stirling. Connemara, Ireland.

Except for the last, I see no provisions for children, for childcare. What on earth are we meant to do with our offspring during these sojourns, especially those of us who are single parents? After decades of feminist critique, and a rich body of more-recent thought on the critical importance of the work of care within society, it seems that proper writers are still supposed to be free of the plebeian ties of home, and caregiving, and the school year, and the relentless call of the mamma.

The thinker and writer as a provider of care seems not to exist at all in the imagination of the grant-giving Gods. While is why Betsey Cornwell’s residency seems so radical — it roots the writer, and the vulnerable writer in particular, squarely within the act of providing care. In this retreat, the children can come with.

But even that last, generous one, involves the moving of the self from one’s current location to another place, the removing of one’s body from the familiar to the unfamiliar, and one’s brain from the place of routine and everyday life to the new.

I contemplate the many ways in which the granting of time for writing is tied to the requirement of moving to a new place to write, and I find myself asking, for myself, but also for the many other writers who just want to or need to write while at home and not in Bellagio:

Is thought elsewhere?

The current granter-industrial complex certainly seems to think so. It is elsewhere, and for the most part without childcare.

How did we move from that proverbial room of one’s own and an income to a room away from home and an income?

And what have these many, many elsewheres done for thought itself?

It is not very new to note that the ability to go elsewhere, the ability to pick up and take off for three months, for a year, without dependents, privileges certain types of thinkers and writers in what is of course an already privileged sphere. It also privileges those who are not deeply enmeshed in everyday acts of caregiving — of children, of elders, of gardens, of animals, of friends, of communities. For caring for children is only one form of caregiving in the world, and there’s certainly no need to celebrate it as the ur-form. Even as a single mother, I’m less interested in the narrative of the single-mother per se, and more interested in advancing the narratives of those involved in primary caregiving for any kind of human and non-human other, for the first is a subset of the second, and it would behoove grant-givers to allow the entire group to find more time to create, at home.

The at home is key, for primary caregiving requires an everyday presence, a nurturing of ties that are not easily pulled away from. It is not a coincidence that most of the writers I see easily moving off on these lovely-sounding retreats are men. A whole lotta dudes. It is not a coincidence that it is also often the childfree, but here, again, I don’t want to privilege parenting as the only form of caregiving that keeps one tied very closely to home.

An elderly parent, reliant on their caregiver, might be much harder to pull away from than a 9-year-old-child. The carer for a pack of street dogs, in those cities where animals have not yet been interned and excised and eliminated wholescale from the city’s streets, is required to maintain an almost-daily presence in a situation where extended absence could mean the pound and possible death.

Sleeping strays during lockdown, Delhi. Caregivers risked arrest to make sure they were fed.

People involved in the daily nurturing of gardens, of trees, of plants, of land, know how precious these ties are. Some people even nurture whole cities. I’m thinking here of the writer Arundhati Roy, who once said of crafting her second novel The Ministry of Utmost Happiness in the great, sprawling city of Delhi, “I never want to walk past anyone; I want to sit down and have a cigarette and say, ‘Hey man, what’s going on? How is it?’ That is, I think, the book.”

To write Ministry, Roy did the opposite of retreat. Rather, she proceeded, and left her wide South-Delhi lanes to write from a small room in one of the densest and oldest parts of the city, moving more deeply into home, rather than leaving it.

The focus on requiring people to move elsewhere to produce thought then, seems to privilege thought that is, for the time of its production at least, removed from care. What might this end up doing for thought itself?

Perhaps it is time for us to consider how the privileging of writing crafted elsewhere might have impoverished writing crafted at home. The requirement of pushing off to Provincetown seems to pull primary caregivers, of any kind, out of the pool of writerly candidates, because while they would love, more than anything, the gift of time, they simply can’t go anywhere else.

Perhaps there’s a new kind of residency that needs creation. Particularly at an aching moment in the world where acts of relatedness and care need to be centered rather than left so very out of the thick of things.

Here’s a new take on the Janis Joplin song.

Oh Lord won’t you buy me a writing retreat. Not elsewhere. At home.

Childcare would be sweet.

Of course, the act of writing takes time, and focus, and concentration.

The merits of going away from all that takes away from these things are many. I’m writing this now at home in stolen moments between grading and my daughter’s calls of mamma, those periodic cries that seem less purposeful communication and more general bird-call, a sound that our young seem primed to make continually, just because.

I know well that my concentration is fragmented. Focus is dissipated. I’m not a good proper writer sitting undisturbed in a library or surrounded by the life of a great city in a cafe. I’m in a bedroom, I’m slovenly, but not in a sexy-unkempt-artist way. There’s no cigarette. Everything droops. Thoughts break. Sentences come, promising, urgent, fully-formed, and are lost, between first mama and sixth mama, never to return. And every writer knows that losing that from-the-ether, revealed-in-dreams, fully-formed sentence is akin to winning, and then losing, a minor lottery. Every fucking time. And-there’s-another one gone. Mama.

The Thinker, New Delhi, April 2020

These are not ideal conditions in which to produce perfect sentences. Within which to produce crystal-clear, analytical arguments. And yet, and yet, there’s so much that writers who are deeply enmeshed in acts of caregiving bring to the table that no one else can.

I’ve already talked about Arundhati Roy, and her nurturing of a city. I’m thinking of Robin Wall Kimmerer, whose biographical note on her author website begins with the fact that she is a mother and continues on to “Scientist and decorated Professor,” all three together. Braiding Sweetgrass — a powerful call for re-imagining the relationship between human and natural worlds — is the kind of work that emerges when thinkers and writers are enmeshed in complex interspecies systems of care.

I’m reminded of Braiding Sweetgrass when I think back to that strange, singular time during the pandemic, when the walls between work and home collapsed. Those were painful, impossible times, and yet, for many who were lucky enough to have a modicum of childcare at home — as I was deeply privileged to have during lockdown — there was something precious and rewarding that also emerged from thinking and teaching and writing at home.

I heard the same from many others; and we have all struggled to find the vocabulary to talk of that strange time. In the midst of the horror, the sorrow, the loss, for many of us there was a sharpening, a clarity of purpose, a deepening of ties within the home, and the yearning for more ties with the world outside.

So much clutter was cut out, so much relatedness desired. Like most teachers, I hated online teaching as it dragged on interminably, but I remember the first six months into lockdown teaching my first full semester of pandemic classes, no separation between home and work, and feeling a fullness of purpose I had never felt before.

Even as my consciousness was even more fragmented than usual, because I was deeply lucky and deeply privileged to have experienced the first phase of lockdown with my daughter’s extraordinary caregiver Hemanti Dungdung living with us, the pull between work and care, between teaching and parenting, allowed for something beautiful to emerge. This is what it might be like if writers who were also carers were allowed to stay home, and were provided with a generous caregiving stipend.

These things are hard to measure, but I know that I have never taught better than I did that semester, and that I will not teach so well again, and I say this, I who put a very great stock in teaching.

I was at home in Delhi, teaching an anthropology seminar, Magic, Science and Religion, in the mornings, and an English-as-a-Foreign-Language seminar in the afternoons. Zygmunt Bauman’s Modernity and the Holocaust in the morning, Frederick Douglass’s My Bondage and my Freedom in the afternoon.

In between, veggie-face — a game a friend invented that I would play with my daughter. We would lay out a clean sheet on the floor and then lay out all our washed and disinfected fruits and vegetables to dry, but in the shape of funny faces. All that I was teaching, all that I was doing, seemed more precious, as well as more urgent, even if more isolated, and more difficult, because of that confluence of the world and the home, because of that confluence of veggie-face and global history. It is hard to work at home, but work made within the constraints of home has a different, and much-needed, flavor.

Creating Veggie-Face between classes with Ruya, inspired by Shoili Kanungo

I’m thinking of Toni Morrison, in her early years, single mother, editor, writing in the wee hours of the morning before her kids woke up. Editing itself is caregiving of another kind. She took care of her children, and she took care of the words of her writers, and somehow enmeshed within those worlds she produced The Bluest Eye. It was many years before she could focus on writing alone.

With even a small childcare stipend, perhaps we would have seen more early works from her, and maybe somewhere, someone is writing words of equal measure, in between shifts, with a child hanging off their tit, or from within a nursing home where they are patiently feeding a parent with Alzheimers their meal, spoon by spoon, trying to remold their connection with them, memory by memory.

Somewhere, in a city like Delhi, an architect deeply involved in everyday animal rescue is dreaming up plans for what they would build if non-human animals were their clients — an arial walkway connecting forested areas in the city for Rhesus Macaques, a skyway of birdfeeds for the city’s Shikras. There’s something about granting the people who can’t leave home the time to write at home that produces writing that is different than that which is produced on retreat.

It may be that the consciousness of a writer who is torn between paying work, caregiving, and writing is necessarily more fragmented, less productive, less efficient. But it is precisely from that fragmented, divided consciousness that the caregiving writer’s insights emerge, and those insights are likely quite different than those of the writer and thinker who is able to craft in solitude. They are born of constraints, of exigencies, of rootedness in the lives of others. Of a toughness and a persistence against the deadening routines of the everyday. This is writing with tits.

I’m not arguing that one is better than the other, but rather I posit that much of human thought and writing has emerged from those who are able to keep a level of distance between them and everyday acts of care. Our core understandings of the writer and the thinker seem to imagine them as figures who are detached from the world. Perhaps it is time to give writers and thinkers who are everyday caregivers a bit more support, and at a larger scale.

Because we need the support.

Writers who are caregivers can produce important work in a deeply damaged world, precisely because they are always torn between the sentence and the mama, or the semi-colon and the bark. There is a kind of fragmented consciousness of care that should be given the chance to create more thought in the world.

But if this fragmented consciousness, torn always between acts of care, and acts of writing, produces a different kind of care-focused thought, there is only so much it can fragment.

There’s a sweet spot between being so put upon that you simply cannot write, and between writing in full retreat, that can produce something extraordinary, and worth supporting. And it is this sweet spot that funders should try to nurture, at least in part. Sure let us continue with the retreats and with the residences, sure, but also nurture more writing from people who can’t leave home. Allow for more writing that is rooted in relatedness, in care and its urgencies, rather than detached from it. Thought is not only elsewhere. Thought is at home.

Oh Lord won’t you buy us a writing retreat. Not elsewhere. At home.

A caregiving-stipend would be sweet.

Give time. Let caregivers who are creators make in place.

“Now is the time of Monsters.” New Delhi, 2019. Pancake on Plate.